LATIN AMERICAN LITERATURE TODAY

December 2023

Love for Life: Notes on Giannina Braschi and United States of Banana

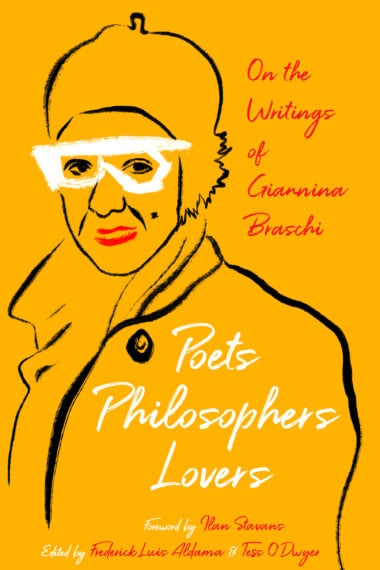

Where is Giannina Braschi’s philosophical fiction taking us? And I say philosophical fiction in a gentle attempt to define the vast Braschian horizon. When analyzing any text by Giannina Braschi, if there is anything that critics agree on, it is in the fact that is extremely difficult to delineate her kaleidoscopic gaze on humanity, her theatrical performance, since it sustains a constant movement through which the characters, actions, and languages are transformed. In her epic poem Empire of Dreams, Braschi says that we depend “on the movement of the waves of the sea. We imitate the nature of the sea.” And it might very well be precisely this flow what makes her work timeless. Palabra en el tiempo. She flows to love and loves to flow. Motion to continue. To continue creating the “hard-hitting, no-holds-barred, mind-expanding story-worlds” that Frederick Luis Aldama describes in Poets, Philosophers, Lovers: On the Writings of Giannina Braschi. No strings attached. No hidden agendas. There is a poetic logic that encompasses the flow of her work. What is it and where is it taking us?

First, it takes us to a liberation. In her allegorical postcolonial novel United States of Banana, the autobiographical character Giannina, along with Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, go on a mission to liberate Segismundo, who is imprisoned in a dungeon beneath the skirt of the Statue of Liberty. Remember Segismundo, from the seventeenth century masterpiece Life Is a Dream by Pedro Calderón de la Barca? He is the Prince of Poland who is imprisoned in a tower by his father, King Basilio. As a metaphor, we know that liberating Segismundo means not only political freedom—Puerto Rico free from the US—but also ontological liberation, freeing oneself from all those strings attached and hidden agendas, something higher than “material dispossession.” Even the Statue of Liberty needs to liberate herself from her condition as a commodity: “they bottled your essence so they could sell you […] But once your genie is out of the bottle, you will become a creative process again. Your genie wants to be liberated.” Giannina points to a saturation of modernity and a possible horizon or new reality beyond late capitalism that is “free from freedom.” Free from the imperial aspirations of the USA and from their hypocritical notion of freedom at the service of capital, always sniffing around some kind of economic profit. Free from ignorance. No more colonial structures. We need to tear down walls and engage in constant dialogue. We need new forms of interaction and communication. We need a new reality. Therefore, we need to create it.

Creation as Revelation

In “Declaration of Independence,” while the characters are sailing to the Isle of the Blessed in the Statue’s crown, Segismundo, Zarathustra, and Giannina start a dialogue on existential and ontological questions related to being and art. Giannina calls on philosophers, poets, and lovers and declares that languages are alive and nations are dead, and that the “powers of the world are shifting,” that “creation is taking over representation” and that “creation means discovery of a new reality that exists but that has not yet been noticed.” This discovery is only possible when “the words are alive again” and “the verbs are in revolt.” In this multifaceted entity called United States of Banana, a mirror with a hundred eyes, the readers are confronted with the creation of alive and revolted words, worlds, and underworlds that the characters of this novel experiment in their quest for liberation, precisely, from the mentality of domination that shamelessly breaks the creativity that is needed to discover new realities. Can we notice a latent new reality in Giannina’s creation? But what could be new?

The essence that seems to be constant in the flow of her work is love. Giannina declares, “Love is what is new—so old and necessary—[…] the missing link in this culture of destruction and death.” The culture of the present “as here and now—is dying—is already dead.” She loves what is alive. It’s all about creating ourselves and about finding ways “to communicate with what is not isolated and confined to a product dated by the market of isolation and death.” It’s all about love and emotions. “Emotions are back. And emotions are talking.” Giannina confesses that she has “high expectations of love—when I love I really love—” but admits that she can’t love what wants to destroy her, what leaves her in the margins. She cannot love what doesn’t let her create herself.

On Love and Eros

When Giannina, Zarathustra, and Hamlet approach the Statue of Liberty, the Statue appeals to the notion of flow and movement when she explains that something is changing. And at one point of their politically and philosophically rich conversation, with the liberation of Puerto Rico always in mind, Giannina tells the Statue that what she desires most of all is to love. And confesses that she tried to love the Statue, but “to love you”—says Giannina—“was against my better self because you never wanted the best for me.” Quite the opposite, the Statue always wanted less of her, to the extent that it thwarted spiritual progress. And how did it thwart spiritual progress? By making her crave what she does not want or need, by making her forget who she is and who she was and, therefore, debilitating her intuition. For Giannina, spiritual progress comes out of creative energy or intuition. Its debilitation would take her prisoner, in the dungeon of liberty, of what is denying her becoming.

Later in this fantastical odyssey, when Giannina sends Hamlet to Hotel San Juan to “study with Socrates how to become a good man,” the two characters engage in a fluid dialogue about how to achieve happiness during adversarial times. Hamlet tells Socrates that Giannina sent him to Hotel San Juan to study “how to become a happy man.” From “good man” to “happy man.” Plato’s Symposium is present: Aristophanes, in his speech on the power of Eros, calls him a helper of humans and a “physician for those ills whose cure would be the greatest happiness for the human race.” But the Socrates of United States of Banana can only take Hamlet as a disciple after he consults with his creative daemon and with Diotima of Mantineia, who “stopped the plague from entering the city for more than ten years […]—a visionary—a wisdom seeker—a seer—a prophet—a midwife—a philosopher—my teacher of love.” Giannina acknowledges Diotima as the one who taught Socrates that “love is not a God—because it is a desire—never full, always needy—an intermediary residing between heaven and earth—between plenty and necessity.”

In the final section, “Declaration of Love,” Giannina petitions Diotima to open the doors of the Republic to poets, philosophers, and lovers. Diotima provokes the mood for love: “I only provoke good things.” But she needs to be created first in order to be discovered and give herself to us: “I’ll give myself to you, after you create me—create me first, then you can discover me […] I am inclusive—I don’t exclude possibilities […] And to be wise is to allow all the possibilities to exist—and to exist in all the possibilities that you can imagine—and then you create those imaginations—and after you create them you watch them exist in reality.” Here’s creation as discovery of new realities that exist but need to be noticed.

United States of Banana ends with the “Eradication of Envy: Gratitude,” a dialogue between Giannina and Hasib, a taxi driver. When he asks her what she learned from Socrates, she says she understood that she had to follow her creative daemon. She highlights the fact that Socrates was also a poet against envy, and he would negate it by following “the line of thought of the intuition.” Intuition is the negation of envy, the positive energy that “envy kills when it refuses to see the rainbow in the sky.” And a rainbow is the installation of an intuition. She asks herself what it is that philosophers envy about poets. She answers that what they envy is that “we are capable of love” and that we have the power inside us to do it. They envy the poet’s intuition, but envy will be canceled by the triumph of intuition against it. Love and the capacity to love will prevail.

Taking a cue from the ending of Plato’s Symposium, United States of Banana ends with the doors open to a crowd of revelers “marching in—knocking on the door—from the beginning of The Symposium to the end––all those people entering the same house of wisdom and wine––all drunk on life––no doors closed––all in different degrees of light and life––in layers of colors and depths of soul––in progression into the limelight––all moving––knocking—and entering––all talking––drinking––sleeping––dancing––and leaving––entering and leaving––the passing of energy from the individual to the multitudes––from the multiples to the single-handed.” We envision the proposal of an attainable utopian world where love is not possession or domination of the other but acceptance of their otherness and a possibility of good. The doors of the house of wisdom and wine opened to the masses “all drunk on life.” One can also think of Charles Baudelaire’s poem “Be Drunk.” It’s an invitation to get drunk on life to escape the pressure of time, to connect to our surroundings and experience everything everywhere, loving life, loving love, loving everything and everyone. “Be drunk, be continually drunk! On wine, on poetry or on virtue, as you wish.” Be drunk on love. Drunk on Giannina.