LATIN AMERICAN LITERATURE TODAY

December 2023

Los picaportes de Giannina

- por Sarah Ahmad

“La última vez que visité a Giannina, me mostró ocho picaportes que parecían joyas, apoyados en su isla de cocina, todos de diferentes colores y tamaños, ordenados prolijamente en dos filas de menor a mayor altura, como en la reunión escolar de cada mañana. Acabo de comprarlos, me dijo entusiasmada, ¿cuántos más crees que debería comprar? Miré con atención los picaportes y sostuve uno color azul zafiro profundo que atrapaba la luz del río Hudson en mis manos. Mientras lo devolvía a su fila obediente, le respondí que sería lindo que comprara cuatro, y ella asintió lentamente, para hacerme saber que estaba de acuerdo, como si el número que yo había mencionado tuviese algo de pomposo, como si tanto ella como los picaportes presentes hubiesen estado esperando ese anuncio. Cuatro picaportes más...”

Click to

Giannina’s Doorknobs

Giannina’s Doorknobs

- by Sarah Ahmad

The last time I visited Giannina, she showed me eight jewel-like doorknobs resting on her kitchen island, all in different colours and sizes, lined up neatly in two rows in ascending height, like morning assembly at school. I just got these, she told me with excitement, how many more do you think I should get? I examined the knobs, holding a deep sapphire one that was catching the light from the Hudson River in my hands. Placing it back to join its dutiful row, I told her four would be nice, and she nodded, slowly, in agreement, as if the number I had named was somehow portentous, as if both her and the existing doorknobs had been awaiting this proclamation. Four more doorknobs.

As a young reader, being able to talk to the person who had written a book I loved was inconceivable. I grew up vagrantly across military bases in India, and most of my reading was sourced through the holdings of the libraries at the various cantonments, squirrelling into dusty shelves to retrieve clothbound, gold-stamped hardcovers that sometimes had been last checked out (or issued, as I was used to saying) by a British officer named Smith or Evans. Prone to fanciful narrations of my own life as an Artist (or what I hear now is main character syndrome), I would touch and read these books with gingerly devotion, as if in reading them I was communing with those who wrote them, wanting to make as good and attentive of a first impression as the milky, muscular hands I pictured having preceded mine in holding their spines, brushing gently over the sentences that I imagined having grown older, wiser, lonelier in the years they had spent between readers.

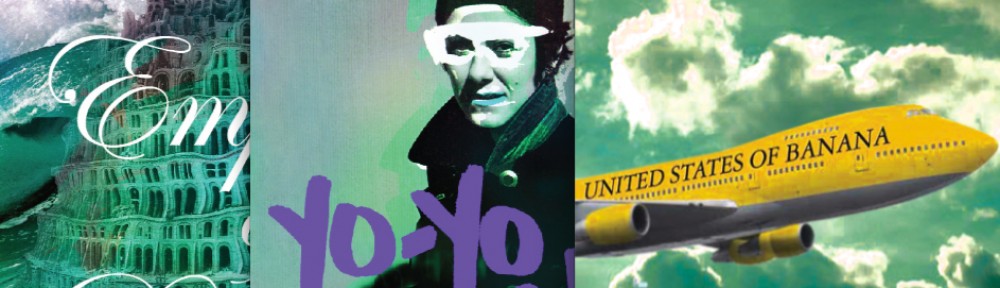

I found Giannina Braschi’s Empire of Dreams in a space both dustily similar to a quiet military library in small-town India and wildly different and opposite in its abundance—the magically crowded Grey Matter Books, the bookstore beneath the water tower that I accidentally always call lighthouse to friends driving me over. I had encountered the title while reading scholarship on cities, empires, and colonization, so I recognized the book instantly. Though I knew I was going to take the book home, I perfunctorily did my first-line-test, thumbing across the introduction to the beginning: “Behind the word is silence. Behind what sounds is the door.” Reading Empire asked me to be an awkward acrobat, trying to match Giannina’s intensely comic and brash leaps from line to line, the text crowded with characters who move on to caricature themselves, pages that are addresses of buildings, contradictions that believe so firmly in themselves but are, in fact, not seemingly in tension with each other at all. I am rather resolutely not a playful writer or reader but was seduced by Giannina’s dollhouse of an empire, rambunctious and elusive. Instead of the familiar joy of being alone with the quiet of a book, a solitude I have relied on for years, opening the pages to her poetry thrust me onto a hectic stage, a deer in the headlights as clowns, kings, witches, rabbits, a shepherd in a beret whizz and whirl past. In Empire of Dreams, I find the names I had treated as sacrosanct as a hungry, young reader—King Lear, Rimbaud, Divine Comedy—except here, they were licentious, grabbed within the vortex of the unruly New York the book charts and populates. Or, as Giannina writes, I want everything. Everything. Everything.

As tends to happen in New York, I was running late the first time I was on my way to meet Giannina. I was nervous—I had realized she lived in the building towering over David Zwirner, one of my favourite galleries in Chelsea, and wanted to arrive as unruffled and proper as possible. Before getting on the bus that would drop me off around the corner from the river, I stopped at the Union Square Farmers’ Market for some peonies and glistening strawberries. There was no doorbell, just a small knocker that I tentatively used to announce my delayed arrival. A few seconds later, Giannina opened the door with a smile, ushering me into her living room full of objects that, she said, she loves and that love her back.

When we were planning to meet, she had said come to my house in a declaration that I felt kinship with, as if meeting her would be incomplete without meeting her house and the objects she collects so joyfully. I was introduced to these objects—the lamp that turns into a chair, the art on the walls, the music box that Giannina wound up to play a tune, the busts of Apollo and Dionysus that perch over her writing desk, the books that spill over the shelves and desk around the yellow legal pads that she wrote Empire of Dreams on, in longhand, sheafs of them, notebooks filled with her thoughts on what she was reading. Around her, too, I was an awkward acrobat, just like while reading Empire, except it is the awkwardness of childhood’s hungry playfulness that being around Giannina pulls center-stage. We talked of mothers, creatures that guarded us growing up, our first walks in New York, lovers, $18 haircuts (mine), and writing. As the sun dipped over the Chelsea piers outside the window, the strawberries lying on the marble of the kitchen island deepened in colour, and tempted us, so we sat quietly and ate them with absolute attention.

Even though I hunt for them with an obsessive and perpetual fervour, I always believe it is the book that finds me. Most afternoons of my pre-teen years, I spent as an eager, unofficial volunteer at the library of whichever base my father happened to be posted to, alone with Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Maxim Gorky’s mother, and William Somerset Maugham (who, as my mother used to remind me for years, was also a doctor as well as a writer). Of course I barely understood what I was reading; all I knew was that I felt a devout calling to words and that the books that carried these names were very good at this calling. As I sheepishly look at (or remember) my earliest writings, it is obvious that I was writing to place myself within the coordinates of the worlds I read through the most childish of tools. Nearly all my “novels” had white-girl-protagonists named Sierra who lived on Elm Street; what I knew how to describe was far-flung from what I experienced.

When I finally left Giannina’s apartment, it was evening. I was close to The High Line and decided to finish the half-nibbled babka in my bag from Breads Bakery while taking a walk. My first walk in New York, the one I had told Giannina about barely an hour earlier, had included the elevated park. I had walked down to The Whitney from The Met, both necessary and predictable first-stops in a debut exploration of the city, and had decided I would allow myself to spend $15 on my Day in Manhattan. Most of this budget was spent on finds from the dollar carts outside The Strand and Alabaster Books (my first favourite bookstore in the city), a slice of pizza en route from Union Square to Chelsea, and I preciously spent the last few dollars on an ice-cream sandwich from a cart. At that time, the apartments around the park were not fully constructed nor as many, so I was able to peer at their smooth glass surfaces with undisguised marvel. Though many years and longitudes were between me and my childhood, I had (un)fortunately not outgrown my main character syndrome and remember feeling electrically aware of being a Young Writer in New York with a backpack full of hardcovers, crumbs of the most delicious ice-cream sandwich I had ever eaten melting onto my carefully chosen Old Navy sweater, watching the sun set over the Hudson. What I found most seductive about New York was how singularly outlined my own thinking and longing felt against the landscape of the city, what Giannina names the big solitude, being thrown into sharp relief buoyantly.

As I leave Giannina’s apartment, almost seven years since that first walk of mine, I think of her New York and the play-things she makes of that which I treated with such reverence as a child; she constructs the Empire of Dreams, as if a text might be a party, or vanish into a dungeon, appear on a billboard, squelch under a foot, or lie like a doorknob in wait. She writes, you, who are big and small, you, who buzz around like bees swarming and making honey from my beehive, and you, who stop my heart. Inhabiting everything. So full of wings, she says, when I show her a short video of incense unfurling alongside my purple shamrock by a window. Is this how you eat a strawberry, she says, biting into its short green cap.

As a young reader, being able to talk to the person who had written a book I loved was inconceivable; if ever I had imagined it, I had thought that on meeting a writer, I might be able to solve a text, have it answer questions about how it loved or warred with itself, why it chose the words it did, that I would, ultimately, achieve that which I thought one must achieve to follow a calling: mastery. Instead, on meeting Giannina, I have quite the opposite, a text more un-fixed than authorized, a devotion to my own long literary pillage without guarding its objects. Why not, to a lamp that turns into a chair. Why not, to doorknobs unattached to the duty of opening something. Why not, to a slow and complete devourment of deepening strawberries. And now it’s my turn to rock from side to side.

Sarah Ahmad was born in Delhi and grew up across the Indian subcontinent. She is poetry editor at Guernica and a PhD student in literature at the UMass-Amherst, where she works on feminist-queer architextures in contemporary transnational literatures and writes in-between poem-prose beings. She has been a contributor to the minnesota review, Poetry, The Margins, Gulf Coast, Muse India, and other journals.